No single phrase has ever done as much damage to the profession of sales as ‘selling ice to an Eskimo’ has. How many times have we heard someone describe a great salesperson, and add this phrase to highlight his/her sales prowess?

In reality, succeeding in sales is a much different (and complex) process. For starters, it absolutely does not require you to sell ice to an Eskimo. There’s a different profession for that, and it is fraught with risks of prison time.

In this blog, we will stick to the more acceptable ways of selling (difficult, nonetheless), and try to look under the hood of a well-oiled sales machinery. We will focus largely on the workings of a ‘sales team’ rather than individuals, and talk about the key questions that most entrepreneurs face while setting up an enterprise sales function.

Early days – The Passionate Sale

In the early days, most entrepreneurs sell by themselves, and that is indeed the right strategy to go with. Building and selling are core functions of a business, and the founder(s) should be fully involved in both. Not necessarily all founders are good salespeople. But it doesn’t matter when they’re just a prototype old and working out of a basement.

The real sales challenge begins when you hire the first sales person.

More often than not, the founders can overcome this lack of sales skills with raw passion and energy. In a majority of the companies, we have noticed that the first ten clients are almost always brought in by the founder. This doesn’t involve any standard sales techniques/playbook until this point. Usually, the founder taps her network, hustles hard, and gets someone to back her idea/prototype. The real sales challenge begins when you hire the first sales person.

From that point onwards, you’re no longer the only ‘face’ of the company. Of course, the challenges you encounter when you’re going from 0 to 10 sales people will be quite different from the challenges when you go to your 50th or 100th sales member, but there are enough common pitfalls throughout this journey. Irrespective of your size, you’re going to face the following existential questions:

-

- Sales model

- Demand generation

- Coverage model

- Pricing

- Compensation and incentives

- Sales funnel management

Starting with the ‘Sales model’ in this blog post, and we’ll try to discuss some of the frameworks for making a sound decision in each of these cases.

Sales Model

This is the most fundamental question facing any sales team. What is the typical journey in your sales process? Does your customer automagically land on your website, and after a series of well-crafted steps, decide to press the ‘sign-up’ button? Or does she need a more human touch -persuasion – whether in the form of a face to face meeting or over a call?

How will you initiate this discussion – will your sales team make cold calls, pay cold visits, or would you set up a lead generation team to pass on qualified leads to your sales team? How do you even decide that calling is the best measure? What about events? The list of these questions is seemingly endless.

There’s no right or wrong template to answer these questions. But as you look for the best approach that fits your business, there are four fundamental rules that you must always adhere to:

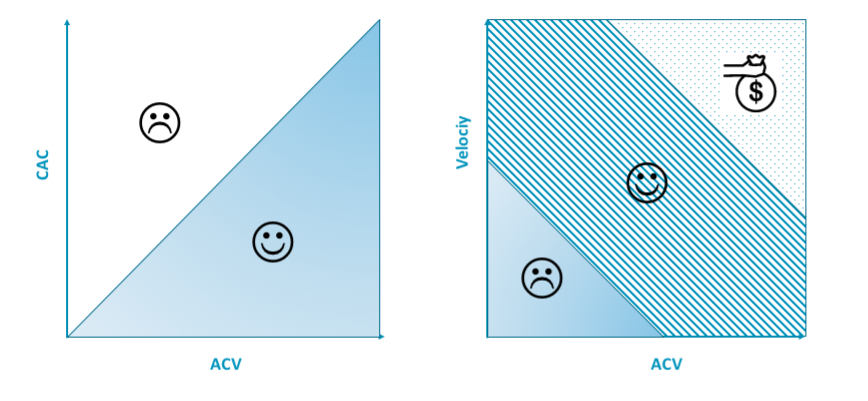

Rule 1: Sales Cost must always be aligned to sales value – Often referred to as CAC and LTV/ ACV – there should be a direct correlation

Rule 2: Sales Model is NOT independent of the product strategy and the choice of target segment

Rule 3: Sales velocity should be inversely correlated to sales value, i.e., your lead to closure time and LTV/ ACV

Rule 4: There is no other rule – you get these right, you are in business!

This looks deceptively simple, and that indeed is the idea. You’d be surprised to know how often people go wrong with the basics.

Rule #1: CAC and ACV

Getting the CAC and the ACV to align is critical. More often than not, start-ups find themselves in a situation where they have high CAC and low ACV, and keep hoping that the J-curve on ACV is right around the corner. In real life, it rarely happens!

Let’s take a few examples (Real ones, company names hidden):

1. An enterprise software company we worked with was selling its product to large global enterprises or government organizations. The product was able to demonstrate value, but the price was mostly $50-$100K per customer, with few exceptions. The sales cycle involved tendering process (For Government), bids with partners, demos/ pilots and sometimes services. Given the navigation of complex organizations and partners, they needed experienced sales people who were going to be expensive. All in all – High sales cost, low velocity, low value. Doesn’t work – period!

2. For yet another portfolio company, the sales cycle was long and cumbersome (? high CAC). However, the ACV was $250K+. This was accompanied with negative dollar churn, i.e., revenue went up with time in existing accounts. This company, in fact, did OK on the CAC-ACV ratio

We are not a big fan of the LTV metric. More often than not, early-stage businesses have no clue on what the LTV will be. There are ways to calculate LTV based on churn, but early churn numbers are very misleading. In our opinion, ACV is a much better way to think about your sales model compared to LTV. Also, there are no standard CAC to ACV ratios that are always good or always bad:

– CAC/ ACV of <1 is important for businesses targeting SMBs (that means a payback period of less than 12 months). In general, lower the ACV, lower the CAC/ ACV ratio as well, which means that range of acceptable CAC becomes even more restrictive when ACV reduces. Ideally, it should be <1 for SMB centric businesses, or for that matter any business that has ACV of less than $10000

– As one goes into larger enterprise deals, it is OK to have higher CAC/ACV ratio, in fact, in many cases, it will be more than 2, which means it takes more than two years to recover the initial customer acquisition cost. But that is OK in most large enterprise-centric deals. They are harder to implement, customers have exit barriers, and one typically lands and expands, which means that the revenue from that customer goes up with time.

Rule #2: What comes First – Sales Model or Product Strategy?

The sales model is not an independent set of variables by itself – it is intricately related to product and the choice of target customer segment. Often, the three need to be iterated together.

There is an AI-based scheduling company we have known for over 2 years – they started off by selling to individual users, helping them replace their assistants with this software.

They soon realized that they were not able to get paid, i.e., they had $0 ACV for this software, even though end users loved their product. They iterated, and eventually found their mojo by addressing the candidate interview scheduling process for enterprises.

Despite being in enterprise sales segment, they are now able to close most of the sales on the phone, are upwards of $20,000 in ACV, and can do so at a reasonably low sales cost.

In a different example, one of our portfolio companies started off with a very low ACV ($1-$2K ACV) as they were targeting SMBs in the US, and even though the sales process was phone-based, the CAC-ACV equation was not great. After a few iterations, they changed the target segment to larger enterprise customers who are deploying SFDC, SuccessFactors, Service Now, etc., and increased the ACV by almost 10x, and now have a CAC that is less than 50% of their ACV.

However, in the process of targeting larger customers, they have had to change quite a few things in the product, including a more comprehensive admin module, ability to mix cloud and on-premise deployment, stronger security features, and a whole host of other features.

Rule #3: Value and Velocity

Very often we meet entrepreneurs who have a very nice CAC/ACV ratio, i.e., they recover sales and marketing cost in less than one year. However, their growth rates are slow – Slow not in the traditional big company sense, but 100% growth in a year for a Series A company is slow. What goes wrong here outside of not-so-good execution – Sales Velocity!

In particular, we have met many India focused SaaS companies where sales model is Feet-On-Street even for SMB customers for as little as $500 ACV. Given the low cost of sales people, they may be able to get to a break even on acquisition cost in less than a year; however, the friction in the sales process makes the velocity slow, and that impacts the scalability of the company.

In general, for low ACVs, you want high velocity, which is typically achieved by marketing led acquisition and not sales led acquisition. A great example is Shopify, which had an ACV of $400 at the time it went public and had significant churn as well. The reason they have been able to scale so rapidly that the sales cycle has always been zero-touch.

Here are some of the key variables that impact sales velocity –

Product Scope: How many people will use the product and therefore, how many will need to be convinced? Are these users across functions?

Value Demonstration: How easy is it to demonstrate the value of the product to the end users?

Who buys Vs. Who uses: Is the buyer or the decision maker different than the end user? Is there a conflict between the objectives of the two?

Market maturity/customer evolution: How educated is the customer about their own need, ways to solve the problem?

Integration: To be productive, does the product need to be integrated to other applications? If yes, are these customized/ configured applications, or off the shelf integrations with well-documented APIs?

Implementation pains: How much change will be required in the buyer’s organization as a result of your product?

Channels – The promised land

Any discussion on sales model would be incomplete without the mention of Channel Partnerships. It is the ultimate dream of every entrepreneur to have his products sold by an army of loyal partners or resellers.

Wouldn’t that be perfect? You’ve built an amazing product that customers seem to love already…why wouldn’t someone want to make a ton of money reselling it? It turns out; there are plenty of reasons why.

To begin with, a lot of start-ups chase partnership with large companies with the objective of tapping their massive Sales channel. If you’re doing this, then guess what – you are not the only one, there are plenty of small businesses like you looking for attention from the big guys.

It will take you a long time to navigate to the right person(s), conduct pilots, prove synergy, differentiation, and that they are better off partnering rather than building themselves; and then the spoiler– by the time you do this, your champion(s) in the partner organization may have left the company or moved on to a different role. ?

Even if you get a top shot executive from a big company to sign your partnership agreement, it’s not him who is going to sell the product at the end of the day. It’s the sales guy at the bottom of the pyramid. Consider this; the good ones are already meeting their quota. Why would they change their goodie bag if everything is working fine?

Another question worth pondering over is whether you want to go after the large partners, who have an army of salespeople on their rolls, or consider someone smaller – where you can better influence the sales behavior (but compromise on the scale)?

As you think through these questions, there are two rules of thumb that can be handy:

– Do your sales guys find it easy to sell the product / are they meeting their quota? If not, then forget that a reseller will. Of course, this could be for multiple reasons – bad product design, poor product-market fit, complex sales process, etc. Fix that first, before leveraging resellers.

Remember – Resellers are force multipliers, not force generators. You can’t rely on them until you’ve found your product market fit.

– Do you have a standard sales playbook yet? If not, the chances are that your sales process is still non-uniform. It’s usually a bad idea to bring a reseller at this stage.

Happily ever after…?

Not so soon. Hopefully, by now, you have started thinking through some of these questions. If you’re feeling underprepared, then you’re on the right track. The idea is to get you to the point where you know what you don’t know. Once you’re there, we trust you to be smart enough to figure out the next steps!

_________________________________________________________________________________

Apoorv Singh is currently pursuing his MBA in General Management from INSEAD, France. He was previously an Investment Intern at Stellaris Venture Partners, and also spent 5 years as an enterprise salesperson in a SaaS start-up.