Most startups understand the need to have a product market fit. In this hard journey of building something valuable, it’s that elusive state of nirvana where everything becomes a little bit easier – you start getting more inbound requests, customers start ‘getting’ your product, sales cycle shorten, and you start calling your quarterly numbers with more predictability – It’s the ultimate ‘promised land’ for all product companies. Here’s some battle tested truth about this mythical place –

- More than any other skill, it takes discipline to reach here, and

- It is a state of dynamic equilibrium – you may lose it after you’ve achieved it.

About Discipline

A lot of companies I’ve seen have been at it for years – they’ve been building features after features, shipping on time, debugging religiously, running campaigns, knocking on doors…Basically doing everything that a God fearing, good product company must. Surely they have been disciplined. Yet, they haven’t found that Promised Land. The problem is that while quite a few such companies manage to achieve the discipline and rigor in their efforts, they don’t put nearly as much discipline in figuring out the direction of their efforts.

Most of them start with a humble ambition of ruling the world. They’ve identified a problem area, and have built an MVP (hopefully) that will solve a problem that people will pay them for solving. And then somewhere they lose the plot.

Bad sales (Devil’s) requests

It all begins with a bad sales request – “The Client loves our product, but wants some additional features before they can commit- <Insert feature that kinda sorta look related to your core product, but stretches your skin a little bit more in the unknown dimension>”. More often than not, there’s too much money involved (of course it’s easy to be disciplined until someone puts a bag of money on the table).

Having been on the table for a while, we’ve had the opportunity to work with some of the best SaaS companies across sectors. One such company, let’s call it company ABC, was doing $150K in annual sales when this deal came along – the client wanted something that looked like a natural extension of ABC’s product.

They would pay ABC $360K over the course of 3 years. All ABC had to do was put 100% of its engineering team on this feature development for 3 months. I’ll leave out the details and come straight to the numbers/outcome – they ended up doing that deal. They got the promised money, and also did the big PR splash around it. Nothing went wrong there. Except…guess how many other clients bought that product over the next 3 years? Two. Netting ABC a grand total of $30K additional beyond the $360K.

Funny thing is, it took ABC 4 years to realize that the deal was bad.

Why was it so bad?

Glad you asked…

ABC invested 1/4th of its product/tech/QA resources in its second year of existence to build something that gave them a sum total of $390 (360+30) K in 3.5 years. Since the $360K deal was a three-year deal @~$120K per year, ABC got $120K + $30K (2 new accounts) in year 3 of the deal (ABC’s 5th year of existence).

Here’s a rough chart of how VC funded good product companies scale (it’s not conservative by any means, but if you’re building a world class product company, this is the threshold you expect to cross):

| Year 1 | $100K |

| Year 2 | $500K |

| Year 3 | $2M |

| Year 4 | $5M |

| Year 5 | $10M+ |

I firmly believe that what a company builds in year 1, 2 and 3 of its existence will effectively bring in the bulk of its money over the next decade. You simply keep adding incremental features in the remaining years (unless of course, you expand the product line – which is a different topic for another day).

If you build a product in Y2, you’d expect it to contribute anything between 30-40% of the revenue in Y5. Even if we go by conservative estimates, your effort in Y2 should have netted you 30% of Y5 revenue, which equals to a neat sum of $3 million as per the chart above. And since ABC put a fourth of its engineering/product effort in Y2 on this said product request, they should have netted $750K. They ended up with $150K.

Bear in mind that these numbers are extremely conservative – I can’t even begin to put a monetary value to the effort that ABC spent over the next three years trying to keep up the product. You know, the usual drill- the bug fixes, QA with every new release, feature enhancement, API modifications and all. Not just that, they spent countless sales hours and marketing budget trying to push that product to the market. As you add all this up, the scale of this mistake starts to become apparent.

While it’s fairly obvious in theory, let me summarize the biggest drawbacks of accepting bad sales requests:

Time cost – Every day spent building something that your market doesn’t want, puts you back by three days in the race to product market fit. If you spent three months building something that nobody else wanted, then you’re spending the rest of the nine months in the year simply catching up to reach the point where you started.

Wrong precedent – Sales reps are out there to make money. They will push anything that makes money and push hard. If you set the wrong example of what is permissible to push, then you’ve set yourself on a slippery slope of overpromised deals, impossible product requests, and agreements that look like downright service contracts.

Organizational bloat – An organization is only effective when everyone rallies behind the same thing. Any deviation from that path leads to the efforts being scattered in multiple directions. Before you know it, you’re spending more time/effort in everything you do – right from building a coherent product roadmap and doing a thorough QA to building the right marketing campaigns and closing faster.

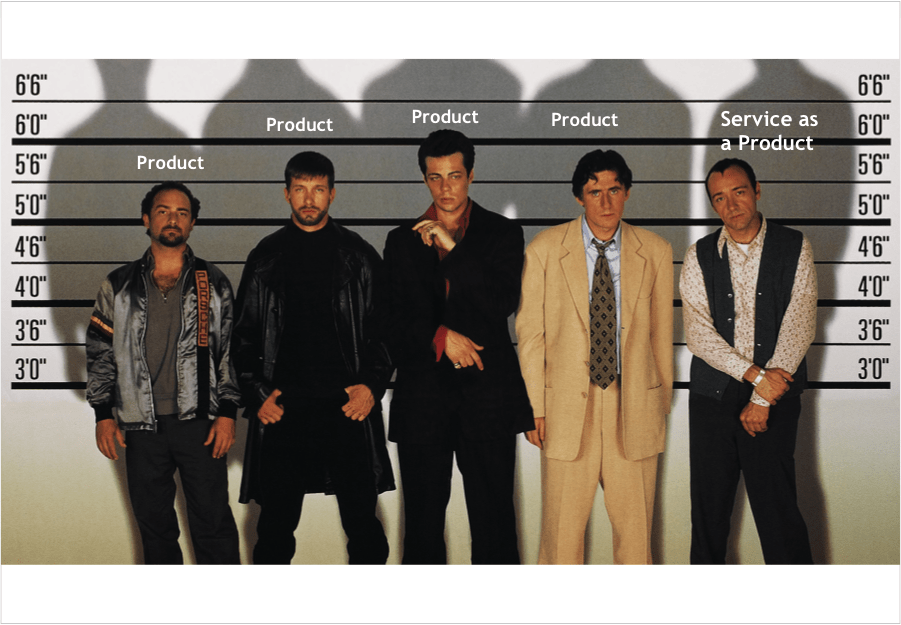

All right then, so now you know about the pitfalls. But here’ something – in the moment when those requests come in, you still wouldn’t be able to say no to them. It’s not as if you have a momentary ‘brain fade’ (sorry, Steve). You are well aware of the pitfalls but still go ahead with those requests, primarily because most of the bad requests are not easily differentiable from the good ones. The bad ones look especially attractive because of the $$ involved. You convince yourself that this is indeed the right direction of the product, and you’re staying on course by choosing to take up that product request.

And that, my friend, is the greatest trick the devil ever pulled

Even worse, you wouldn’t know until a few years later. Such deals will make you look good in the short run. They’ll bump up the revenue, add big logos to your client list, and investors will love it.

“If you’re a SaaS product; look at your last 12 months revenue- if your one time revenue is more than 5% of the overall revenue, then the devil has you.”

The protection spells

So how to avoid the obvious mistakes? You may be disappointed at these steps; some of them are textbook. The trick lies in execution and discipline:

Do it with data – Right from day 1, build a culture of managing a product request sheet. Ask your product guys to put a revenue value, urgency value, etc. against each of those requests. Small clients and good to have features would obviously account for lesser value than larger clients and urgent requests. Bucket the similar ones together.

Tip – Your product managers will almost always have no time to get into client calls and get an accurate view of these columns. That’s why you hire product analysts. If you’re too early stage, have the product manager work overtime to do this. It’s not going to be easy, but totally worth it. If you sell to SMBs, simply put up a form on the website to collect this data. Whatever you do, don’t ever let the sales team manage this sheet. EVER.

Treat this sheet as an airline pilot would treat her navigation tools. It will prevent you from the hallucination and other curious psychological phenomena such as the recency effect, halo effect, etc.

Build a sales culture – Rein in your sales team from overcommitting. Put harsh terms for sales team for deviating from the standard client contracts. As a CEO/sales leader, get in those difficult client meetings and don’t mince words. If you can’t build something, then say you can’t, and explain why. If the client believes in your core product, they’ll still come. If they don’t, they’ll free up your time to pursue the ones who would.

Don’t negotiate with the product manager – This is the hardest bit to execute. Despite the best of processes, it almost always ends up in a slugfest where the most influential sales manager (often the CEO himself or herself) gets to push his/her product request through. The point is, it’s a nightmare for a product leader. She knows her job the best, provides her with all the information she needs to make her decision and then trust her to do it. Period.

Validate- Despite everything you do, you may still end up making product decisions that are ill-fated. Keep an eye on usage numbers, and be ruthless in culling out the features/product lines that aren’t working. Oh, and having 2/500 clients using a feature does not qualify as usage for that feature. No matter how much money someone paid for it.

All of the above steps are easy in theory, but the most difficult to implement. Often, they will go against logic, but you must trust the process. You can take that leeway when you hit 100 million in revenue, and feel like you know the market better than it knows itself.

Till then, stick to discipline. RUTHLESSLY, RELIGIOUSLY, RIGOROUSLY